If you’re working on battery carbon footprints under the EU Battery Regulation, you’ve probably encountered the Circular Footprint Formula. The CFF is how the regulation accounts for recycled content and end-of-life recycling in your carbon footprint calculation.

It’s also one of the most complex parts of the calculation to get right.

This article explains what the CFF is, where it comes from, and why it matters. In a follow-up article, I’ll cover the implementation details—the pitfalls and architecture decisions that make or break a CFF calculation engine.

What is the Circular Footprint Formula?

The CFF is a mathematical framework for allocating environmental impacts between:

- The system that produces recycled material (the previous product’s end-of-life)

- The system that uses recycled material (your battery’s production)

- The system that will recycle your product (your battery’s end-of-life)

In simpler terms: when you use recycled aluminum in your battery housing, who gets credit for that recycling—the phone manufacturer whose old phones were recycled, or you for using the recycled material? And when your battery eventually gets recycled, do you get credit for that future benefit?

The CFF provides a consistent way to answer these allocation questions.

Where Does It Come From?

The CFF isn’t unique to batteries. It originates from the European Commission’s Product Environmental Footprint (PEF) methodology, developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC). The battery-specific version is detailed in the JRC’s Carbon Footprint Rules for EV Batteries.

The formula appears in Section 2.6 of the Delegated Act on carbon footprint rules (part of Regulation 2023/1542, the EU Battery Regulation). This section specifies:

- How to model recycled content in material inputs

- How to calculate credits from end-of-life recycling

- Default parameters for battery-specific recycling processes

- When you can use company-specific data vs. defaults

The Material Flow: Why Six Terms?

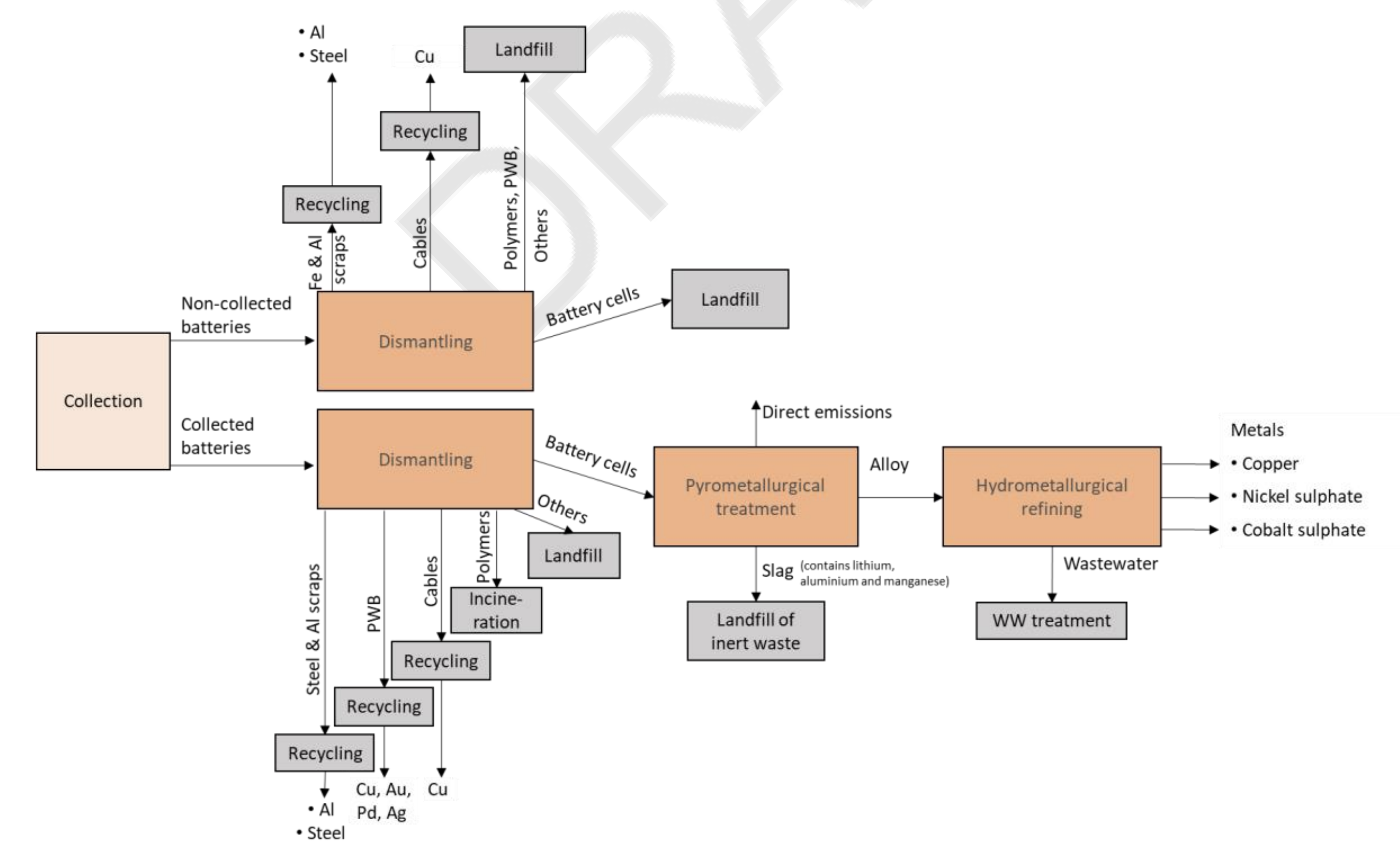

To understand the CFF, you need to visualize what happens to a battery at end-of-life. This diagram from the JRC document shows the complexity:

Source: JRC Carbon Footprint Rules for EV Batteries, June 2023

Starting from collection, batteries split into two streams:

- Properly collected (default: 80% return rate)

- Non-properly collected (the remaining 20%)

From dismantling, materials flow to different destinations:

- Steel and aluminum from the housing → direct metal recycling

- Copper cables → copper recycling

- Printed wiring boards (PWB) → specialized recycling to recover Cu, Au, Ag, Pd

- Polymers → incineration with energy recovery

- Battery cells → pyrometallurgical treatment → hydrometallurgical refining

- Other materials → landfill

Each of these pathways has different recycling efficiencies, quality factors, and emission profiles. The CFF captures this complexity through six terms.

The Six Terms at a Glance

| Term | What It Covers | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Material inputs (virgin + recycled content) | Always a burden (+) |

| 2 | Dismantling credits (housing metals, cables) | Usually a credit (−) |

| 3 | PWB recycling (precious metals from circuit boards) | Net impact |

| 4 | Cell recycling (Co, Ni, Cu from cells) | Net impact |

| 5 | Energy recovery (polymer incineration) | Burden (no credit with default parameters) |

| 6 | Disposal (everything not recycled) | Always a burden (+) |

Terms 2, 3, and 4 are where the complexity lives. They balance:

- The burden of the recycling process itself (energy, chemicals, emissions)

- The credit from producing secondary materials that displace virgin production

Get these terms right, and you’re accounting for the real environmental picture. Get them wrong, and you’re either overclaiming credits or underestimating burdens.

Why the CFF Matters

Here’s what often surprises people: the CFF is a substantial portion of the total carbon footprint.

For a typical EV battery, raw material production (Term 1) dominates. But the end-of-life terms (2-6) can represent 10-20% of the total—not a rounding error.

More importantly, the CFF involves:

- 19 different materials with distinct parameters

- Multiple recycling pathways with branching logic

- Quality factors that adjust credits based on material degradation

- Two-stage cell recycling (pyrometallurgical → hydrometallurgical)

- Separate calculations for collected vs. non-collected fractions

This is where implementation gets interesting. The regulation tells you what to calculate, but the how—the data architecture, validation logic, and edge case handling—is left to you.

The Value of Getting It Right

When you have a robust CFF implementation, you gain something valuable: a validated black box.

Instead of manually tracking dozens of parameters across six terms, you feed in your bill of materials and get back a defensible, regulation-compliant result. You can focus your attention on the parts of the carbon footprint that require company-specific data (like your manufacturing processes) while trusting the CFF calculation.

That’s the goal: make the complex part reliable so you can concentrate on the parts that matter for your specific situation.

What’s Next

In the next article, I’ll walk through the implementation side:

- Common pitfalls that trip up even careful implementations

- Data architecture decisions that make the calculation auditable

- The gap between the regulation’s formula and a working calculation engine

The CFF is one of those areas where the devil is truly in the details. But once you understand those details, you can build something that handles them reliably.